|

Vertical Divider

|

VOLUME 50.1&2

THIS ESSAY IS LISTED AS A NOTABLE ESSAY IN BEST AMERICAN ESSAYS 2017

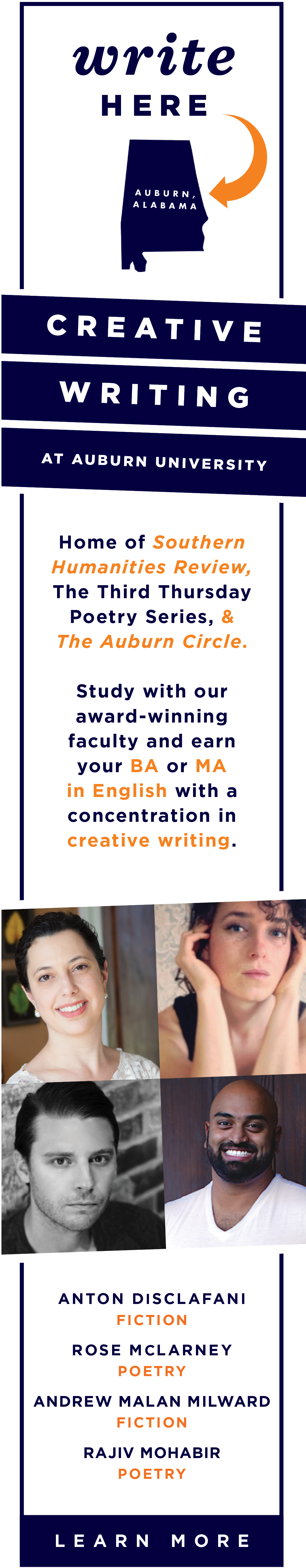

ADVERTISEMENT

|

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|