|

Vertical Divider

While boarding and settling down in the school van, my students talked animatedly about our field trip to Princeton to attend a Claudia Rankine reading, about what they wanted to hear on the radio, and if we could make a pit stop for snacks. The small group was made up of members of my Craft of Poetry and Prose Workshop classes who didn’t have any schedule conflicts that day. The poetry students had read Rankine’s Citizen in preparation for her reading, and the others were attending without any prior knowledge of Rankine or her work besides what I’d said while briefing them about the field trip opportunity.

One of my prose students, a proven and vocal workshop leader, sat quietly in the van, headphones in. I wondered what was up, but I didn’t want to pry, especially with other students around. When we got to the event, however, the student sat next to me and told me about the recent death of one of his dearest friends, a poet, Black Lives Matter activist, and community organizer in Columbus, Ohio. I mention all of this because of how the conversation intensified my experience of listening to Rankine and how that intensification allowed me to reflect on the implications of an undergraduate class reading Citizen. Throughout Rankine’s delivery, I found myself thinking again and again about my student’s friend and the impact of that young man’s life on his community. I began to wonder if the essay about race my student had turned in the previous semester had been encouraged by his friend. I was once again reminded that students write out of their lives, what matters to them, who matters to them. My students weren’t writing for me; they were writing for themselves and their loved ones. I also began to listen expectantly to Rankine with the hope that, in some way, she would speak directly to my student or at least seem to, in order to comfort him. I then realized just how much I was relying upon Rankine in terms of all of my students’ education, how much I wanted them to hear her voice and her words, and not my own. As a teacher, I was giving up teaching for the moment in order to be taught, to sit beside my students in the same row of the theater, to see them listening and to listen myself. I’ve begun to wonder if those moments in which we teachers listen to—and with—our students are often some of the most instructive. At the very least, they tear down the classroom hierarchy, subverting the privilege of educators (educational, financial, or otherwise), and position the act of listening as equally valuable and meaningful to both teacher and student. From this moment on, I began to think about my role as something of a teaching assistant to the faculty of our texts. •

A few years ago, I took Jaquira Díaz’s fiercely rendered short story “Section 8” into an introductory creative writing class. The school I was teaching at at the time was almost primarily white, and many of the students belonged to the upper echelons, to families with high incomes. I was excited about the story, and I wrongly assumed my students would be engaged with the it. “I don’t find the story relatable,” one student said, ignoring our rule of not using the R-word. “I mean, I’m not a lesbian, and I don’t live in Section 8 housing, so what am I supposed to get out of this?”

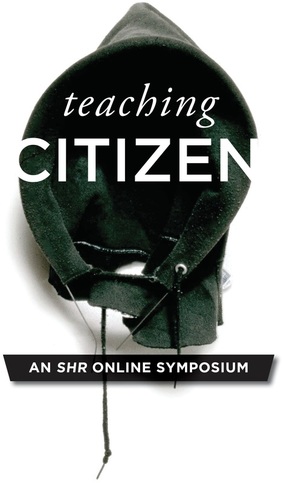

This was the moment when I realized that I should make it my job to bring in more texts by people of color and members of the LGBTQ community, to require the students to do the work of relating, no matter who was writing or speaking in the work. Perhaps this act of exposing students to the lives of others is or should be the additional work of creative writing classes. (I won’t say it should be the “secondary” or “auxillary” act, for it may provide some of the most important insights students experience, both in and after the class.) For that reason, I assigned Citizen the following year, just after it was published. Although I was at a different institution by then, I had a similar group of students. After class one day, one of my only students of color came up to talk to me about the text. “I’ve never had anyone assign a book by a black woman,” she said, which is exactly why we, as creative writing teachers, should assign a book like Citizen, especially as it engages and exposes racial microaggressions, for isn’t the redaction of these voices on syllabi a microaggression itself? •

In assigning Citizen as the first book of the semester in my Craft of Poetry class, I hoped to establish the class as a space in which all the students could contribute and share their individual experiences. At the small college where I teach, the creative writing classes have a more diverse student body than our other English courses. In my Craft of Prose class in the fall, over half the class was made up of people of color.

Additionally, I wanted to establish in my class the act of reading as an act of listening, therefore cultivating all participants’ abilities to listen to one another. Now, I’d like to listen to my students, who can tell you more about what they experienced in reading and listening to Rankine than I can:

|

|

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|