I was pleased to unpack SWOLE with Jerika, who gave me such a surplus of material that I’ll post some outtakes on Medium in a few days. Don’t let this peaceful interview fool you—her poetry is a deafening, beautifully engineered blast of experimental gunpowder.

—Katharine Coldiron

|

|

I dislike revealing that my poetry is so personal and so indivisible from my experience of being alive. I’d like to be cool about it—cool and removed and intellectual. It’s personal not necessarily in content—yes, there are bits of autobiographical narrative here and there—but in the language itself. The poetry’s syntax—the repetition and dialect included—is intimately what I am. For anyone reading my poetry—there it is, there I am—my heaving back and forth through senses, grasping on to anything and everything that feels true. Maybe my reader will get a sense of how overstimulated I am at all times.

I am trying to get over my fear of oblivion. Poetry—the act of writing it (the way I come to it)—is just the chance to say what was here, how it felt. I imagine it’s as close as I can get to flaying myself alive.

KC: Did you have an entire project in mind when you began?

JM: Not at all. I was an MFA student and still trying to figure out what poems were or what poems could be. I spent some time imitating other writers, like trying on hats to see what might suit me. The beginnings of SWOLE were really a bunch of notes, scribbles, letters, and observations. The fragments felt really free and organic. SWOLE was supposed to be a placeholder title, but I’d been reading some text on wounds or trauma. Swelling is the body’s first healing response, a response to stress. Swelling is what happens with too much salt intake, when a river is too full, when a storm gorges itself on warm water and gets really big and punches your city in the face.

I still don’t think of the book as finished. When I do readings, I add or cut away part of the book so my audience can flow through its fluctuations with me. I think if I knew and felt all the things I do now when I was starting to put the thing together, I may not have ever tried publishing it. There’s so much that needs to be said, and I’m just a small part of that.

JM: My mother worked (and still does to this day) as a part of the emergency medical teams for one of the hospitals in the area, so she’s typically working during the storms. We can’t evacuate without her, so we mostly just hunker down and wait for them to pass. We’re used to hurricanes down here.

In 2005, I’d just started high school. It was a little stressful, I think—new environment, new friends, new body doing weird pubescent things. When we first heard there was a storm in the Gulf, it was just like any other. I actually hoped it would come toward us so I could get a few days off school, get extra time to study for exams, figure out if I wanted to stay in the marching band. I still feel incredibly guilty about this—like, maybe if I hadn’t wanted so badly for Katrina to land, it wouldn’t have landed or wouldn’t have been so strong. It makes me feel a little sick thinking about it.

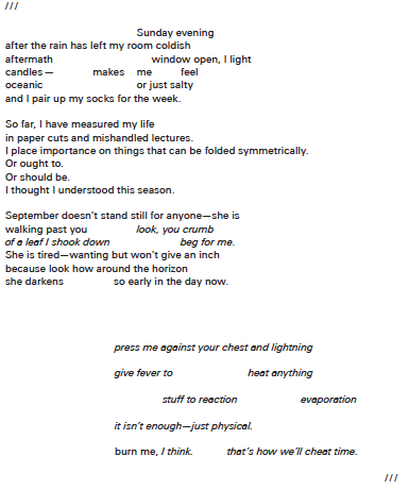

EXCERPT FROM: SWOLE

I went to bed Sunday night as the storm strengthened in the Gulf. It hit Monday morning. I didn’t see my mother until that Friday. I won’t go into the things that happened to me and my family in between—certainly not as bad as what others experienced, minor compared to what others lost. Trauma isn’t a contest, though, it’s worth saying. But I will say that it still rips through me, the sight and sound of my mother coming through the front door after days of being separated. None of us really knew how bad it was because we didn’t have the news, cell phones weren’t working. There was just the radio and a lot of the channels were dead air. Because I was oblivious to what was actually happening, I never really believed my mother was in danger or in any risk. That any of us were in danger or in any risk. It wasn’t until my twenties that I realized how much I could have lost, how close we were to losing everything.

It hurts me a lot to think of what it took my mother to find her way back home, with the bridges being closed, all the trees that fell, all the debris and the water. How alone and afraid she must have been.

I try not to think about it too much, any of it. Not in a ripping-open-wounds kind of way—that fills me with a lot of fear and anger and sadness I’m still not sure what to do with. I do think about how we got through it—as a community. How we’re still going through it, what we’re trying to build to fill what’s been lost, how we’re probably going to still lose it anyway, how we keep trying.

Once my mother got back to us, we evacuated as soon as the roads were cleared. We went to my tita’s house in a different state. I remember flashes of the drive there—along the beaches of Mississippi and Alabama where the roads had opened, just debris and kind of dark. I shut my eyes to it because that’s all I could do. I had a Walkman and two CDs that I just played over and over again. I can’t listen to some of those songs without feeling weird.

At my aunt’s house is where I saw the news for the first time and saw images of what happened to New Orleans. I don’t remember much after that. I think my brain saw and heard the news and then decided to shut off. I think I just slept for three months. I can’t remember what I did to pass the time. It’s all blank, like a part of me went comatose. I didn’t go back to Louisiana and back to school until (I think) November. I was lucky. Mmm, and I didn’t go back to the marching band.

KC: That’s powerful. Thank you for sharing it.

This book has a very specific sound. It’s a cacophonous book, and I mean that as a compliment. Were you thinking of a Greek chorus, or flipping channels on television, or...?

JM: Yes, a Greek chorus or a play or a libretto or a playlist or a score or a mashup of all of those things. Any kind of space where I could attempt to organize seemingly disparate parts and sounds.

During the storm, all we had was the radio. I have a bright memory of turning the dials on the radio back and forth, looking for any kind of human voice, and hearing mostly static. Sometimes music. Then Garland Robinette and all the people calling in to the radio station calling for help or asking for information. I write “why is the water rising, if the storm is gone?” This is something I’m certain I heard come out of one of those phone calls to the radio station.

I took anything I could remember from that time and filled myself with it—stories from other people, neighbors, friends, what I saw on the news, telethons, headlines, signs people posted outside their homes. There are all these images and sounds, misinformation and facts and mingling of traumas.

There were so many voices, some external and some intimate. There was reporting of what happened and then people telling what happened to them and then people telling me what happened to me and then people asking what happened to me and my family and really, not a lot of it made much sense to me then. A goal with the book was to take all that confusion and have it mean something. To not let it all fade to static or as a neat little paragraph in a history book.

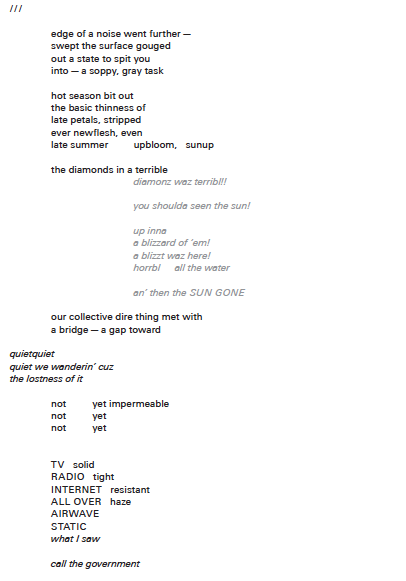

EXCERPT FROM: SWOLE

JM: That’s such a compliment. I definitely don’t see my writing that way. I feel my syntax twists up from how I hear my voice talking inside my head and then I feel like I have to add on to it and put it into different contexts and maybe bring in some other voices for contrast.

I enjoy phrasing that rings in different valences—this explains my pull toward transliteration and repetition. Sometimes I believe that mistakes and accidents aren’t unintended or random, they’re sublimations of the subconscious. In writing, I like to let my syntactic “mistakes” build their own space. That’s real, too, and evocative. It’s as real as anything I write inside of a deliberate constraint.

KC: What works influenced SWOLE? Do you feel like you’re part of a discourse on Katrina?

JM: I was heavily inspired by M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee. If the book (or any book) helps to keep the conversation on Katrina alive and relevant, I’m here for that. Otherwise, I don’t like to see myself as representative of that conversation or any kind of authority.

KC: Do you see the purpose of Katrina literature as recording the event, or interpreting it?

JM: Both. All.

I dislike saying what any literature ought to be, but I do think anything touching on Katrina should work to excavate all the humanity of it. There should never just be one story, one throughline. Nothing buried, nothing silenced or erased. It should never feel too clean or sensationalized.

KC: What can you tell me about the dialects in the book, and/or the place of people of color (as narrators, and as subjects) in the story of Katrina?

JM: In another interview I mentioned how fucked up it is to write anything about New Orleans that’s devoid of its black and Creole communities. I’ll say that again: it’s fucked up to erase black and Creole communities and their influence from this place.

When I was hand-wringing about the language of the book and preoccupied with how it would sound to others, I got a sign from New Orleans herself. I was walking to my car after dinner in Gert Town, and people were out on their porches and steps just catching up. A man with a trombone in his lap greets me, “Who dat!”, and I try to offer him a “Good evening, how you doing?” and he tells me “When I say who dat, you say WHO DAT.” OK. That’s how it’s going to be. It was exactly what I needed to hear.

The breakdown of language, of communication, of rules, of what’s proper—not just in the context of Katrina—shifted everything around in my head. Attempts to sterilize or homogenize or “clean up” languages/musics/magicks felt like an act of erasure. The insult that some vernaculars are “broken” English is not lost on me. Language, too, has been weaponized against those who have not been adequately and politely assimilated to some arbitrary standard.

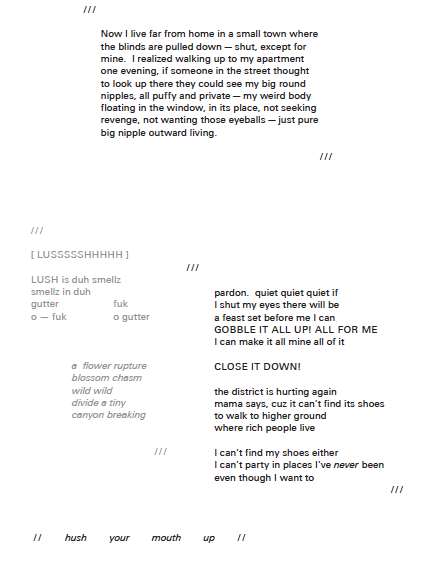

EXCERPT FROM: SWOLE

This mixture of tongues—what people say with words, how they say it, what they mean when they say it—informs my humanity, my reality. Here at home is always the sound of people talking, greeting each other, conversations, things being said to me, blasted through speakers, singing at the top of their lungs, the grocery store, streetcar, sidewalks. How could I not let this be part of the book when it’s so much of my world? I had to think of some way to pull the story away from the authorities, institutions, headlines, and talking heads and back into myself, my neighbors, and my community.

I wanted this whole sound of humans full of breath, heart, anger, song, movement of body, and I wanted to be unencumbered by the fear of the imperfectness of my medium—ink on paper. It’ll never be enough, but I like to think I tried.

KC: What is your triggering subject as a writer? Do you think you got at it in SWOLE?

JM: Most of the book involves circling around and around like…a gaping hole, an emptiness, a fracture—a wound that still feels fresh—lean in to it far enough, just enough to feel its pull, its gravity, and then deflect to another voice, another situation.

Maybe it’s just part of my poetics now—circling round and round the hot, scary stuff.

KC: Like a hurricane with an eye.

JM: I think, like everyone else, there are things I’ve shut away because they’re too painful. You’ll give life to things not easily or neatly put back. Which is why I’m almost ready to put SWOLE away for a while. There are some things I need to reassess, relearn.

In terms of triggering subjects, I’m interested in immigration, borders, families, ancestries, memory as it gets handed down from generation to generation, fantasizing about what an unpatriarchal, uncolonized world would look like (who are the heroes and villains?! who are the authorities?! what are men?!?).

It’s kind of a relief to be working in the new book—which is an exercise in world building, instead of pulling so much from memory/unmemory. I’m still definitely myself and in my own voice, but with a little less pain. Maybe.

|

|