|

Vertical Divider

I’m a teaching assistant at a large, public university out West.

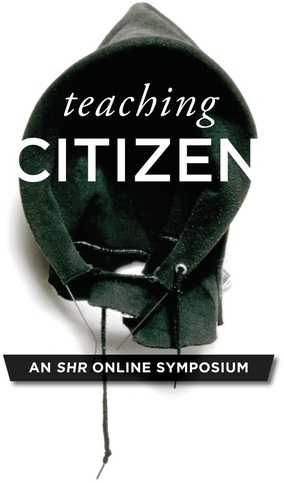

When I accepted a spot at that public university’s M.F.A. program, I was told I would also have my own classroom. During my first year, the program provided me with an extensive composition curriculum, a textbook, and twenty-two undergraduate students. Teaching reminded me of my previous career in marketing: I was selling rhetoric to eighteen-year-old students. Maybe it’s blasphemous to align education with capitalism, but I loved finding a way to make concepts hold; I watched it turn their writing into wonder. During my second year, I was assigned an eight a.m. undergraduate poetry workshop. Choose your own books, the program told me. Have fun. I turned to my mentors for help. One told me, Teach the books that made you fall in love with poetry. Another advocated diversity. A handful of former teaching assistants said they’d found success teaching Louise Glück's Wild Iris, a book I’d never read but had known about since I was an undergraduate student myself. In the end, I assigned these texts in the following order:

I decided this would not be a class about prosody or comparative analysis. This would be a class about creativity and obsession. My aim was to sustain their enthusiasm. If they choose to continue writing after the semester ended, there would be ample time for them to hone their craft down the road.

•

I placed Glück at the beginning. It felt like a soft landing for our introduction to the lyric. We moved onto Rasmussen, and they confronted the subject of this book—his brother’s suicide—with surprising equanimity. We poured over his absurd images and dark humor together, held together entirely with couplets, and they brought forward their own stories of grief. Lee’s mix of prose and poetry about the Korean immigrant experience led us into conversations about shared language and intended audiences. I expected them to say, We don’t really like this, we don’t understand. Instead, one student in the class responded, I don’t expect to like everything. I recognize this is not my experience. And we talked about why. Then we moved onto Seamus Heaney, the poet I’ve spent the most time with. I recognized there was something anachronistic in teaching the Irish laureate’s poetry about The Troubles in order to prepare my class of mostly white, mostly in-state students at a large, public university for our final book, Rankine's Citizen. But with Heaney, I know the historical context by heart; North is the book that made me fall in love with poetry, even if I’ve moved beyond it.

So I asked my students, How do we address experiences embedded in our history, land, and language? How does Heaney balance art and obsession with the expectations of what his communities expected him to perform? I didn't tell them how my personal background—growing up in a small Minnesota town where ninety-five percent of the population is white—left me struggling to know how to teach Rankine without feeling like I was making excuses for my whiteness. I was fighting doubt that said if I didn’t feel comfortable talking about race, I should leave Citizen to the individuals who embody the experience Rankine describes. I should listen. I should wait. But I had the opportunity to bring Citizen into the classroom, and I didn’t want my students to miss out on the conversation because of my own insecurities about getting it wrong. •

The day before our first discussion of Citizen, University of Missouri president Tim Wolfe stepped down amid protests over racial inequality on campus, threats by the football team to boycott homecoming, and a graduate student holding a hunger strike. The momentum behind the movement was generated by Concerned Student 1950—a student group named after year the first black student was allowed to attend the University of Missouri. The group had been organizing protests throughout the semester. Their efforts culminated in an open letter to Wolfe on October 20 calling for his resignation. They also advocated for more black faculty and staff and a racially inclusive curriculum.

I followed the news on Twitter while I sat with Citizen, reading interviews with Rankine and looking over my notes from the semester. The next day, I set aside my lesson plan and brought Concerned Student 1950's list of demands to workshop. When we reached the section that asks Wolfe to acknowledge his white male privilege and to recognize systems of oppression do exist, one of the men in my class asked why Wolfe needed to apologize for being a man. One of the women in my class turned to him and explained, They’re asking him to acknowledge, not apologize. They want him to recognize he’s part of a power structure and has the ability to do something—and he’s not doing it. How did I teach Citizen? Slowly, and with as much context as I could assemble using Rankine’s own words and the references she made to videos that I could track down online: Rodney King, the “Serena Shuffle,” Wozniacki posing as Serena. We did not cover everything. Citizen led us to conversations about Syrian refugees and micro-aggressions on our own campus. The Serena Williams essay pulled us in again and again. I forced us to linger on the opening photo of Jim Crow Road in a Georgia suburb and the final image of the Turner’s slave ship turning into the storm. The night before our last discussion, Jamar Clark was shot dead by police in Minnesota, my home state. Witnesses say Clark was handcuffed and laying on the ground when the shooting occurred. Officers say he wasn’t. His death led Black Lives Matters organizers to shut down Interstate 94 and then occupy the 4th Police Precinct for eighteen days. I watched events unfold on YouTube. At the same time, another video was going viral: Johari Osayi Idusuyi, front and center at a Trump rally, reading Citizen. Rankine told an interviewer that she put a Turner painting at the end of her book because people always say, Well, I didn’t know. It wasn’t my intention. I wish I had known more about this. . . . But Turner knew better in the 1800s. He knew better. I credit Citizen for the conversations it allowed me to have with my students. I credit it for helping us recognize all the ways we aren’t immune from knowing or protesting the racial injustice occurring in our country. And in the end, I credit it for teaching me what I am still learning how to say and the myriad ways of knowing better. |

|

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|