|

Vertical Divider

Teaching a single-author poetry book is a different adventure than assigning poems from an anthology. There’s more information to process: future greatest hits share bandwidth with poems that may be harder to absorb; ordering, epigraphs, and subsections suggest new meanings; there’s an arc to read for, through-lines to discover. These carefully composed slim collections, though, are my favorite way to travel through a poet’s work. Maybe it’s all that intensive concept-album-listening I did as a teenager. I love to consider lyric scenes as part of a larger undertaking.

I teach undergraduates at a liberal arts college, and in most of my poetry courses, I assign at least a couple of these volumes, often recent ones I want to study more closely. I typically place them in the second half of the semester, after close-reading skills become sharp enough to stay in balance with the larger thematic readings students often prefer to do. In an upper-level seminar on African-American Poetry in the winter of 2015, the last book we read together was Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric. This emotionally and intellectually intense book is longer than most single-author collections—extending even to videos on the poet’s web site—so we read it together more slowly than usual, over a week and a half. For our first session, my class read sections I and II, posting responses on the course web site. I put several framing terms on the white board:

This list of touchstone issues synthesized common points in their written responses with my own preoccupations. Memory was a theme of the course, for which I assigned readings and projects of local as well as national interest. Washington and Lee University, founded as Liberty Hall Academy in 1749, gained a significant portion of its endowment from a nineteenth-century bequest that included enslaved people; Robert E. Lee became our most influential college president at the close of the Civil War. The class talked often about these legacies and how the university might better recognize the disturbing aspects of its complex history.

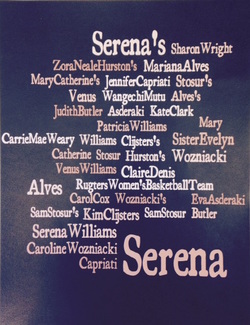

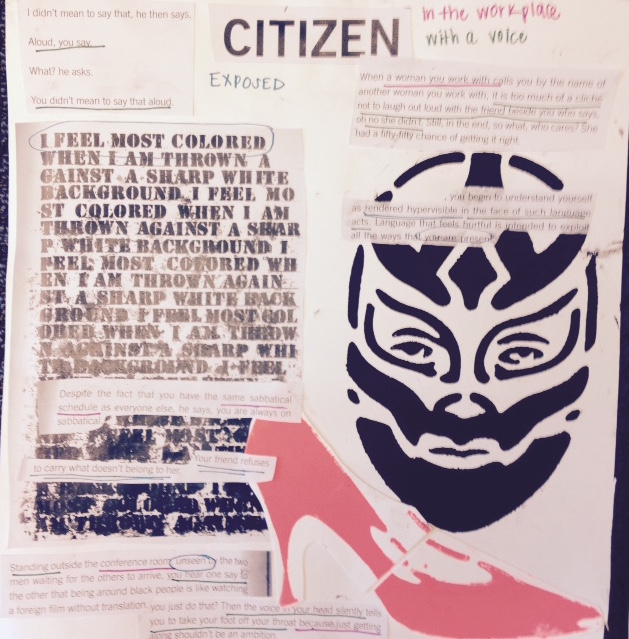

Citizen brought many of these previous conversations to a provocative culmination, but first we had to open a lot of windows: the work presents many linguistic difficulties as well as social and political ones, and most people in the room were just beginning to read contemporary verse. Conversation about poetry often toggles between why and how—the matter and the means—but Rankine’s poetry is both uncommonly urgent and formally distinctive. The experiment of teaching her work involved constant course corrections, as I kept realizing I’d swerved too much into one lane or the other. After noting the marketing description on the back cover—“Essays/ Poetry”—we started with part II, observing its essay-like coherence around Serena Williams’s career. Later, I realized I needed to fill in history about Sarah Baartman, the so-called Hottentot Venus, but we nevertheless had an animated conversation about “commodified anger,” gender, and race in U.S. media. We then compared section II stylistically with section I, in which paragraphs are never enjambed over pages: in the book’s initial suite of writings, each page is a distinct formal unit, more or less a prose poem. The Poetry Foundation’s recording of Rankine reading page 10 (“You are in the dark, the car”) was useful here. After listening to it, and after talking about the term “microaggression,” we discussed that page as a poem: the significance of setting, its shifting pronouns, a refusal—in contrast to later sections—to name emotion. We picked up many of these questions in our next class meeting, during which I also showed them Tony Hoagland’s “The Change” and reported on the exchanges between those poets.

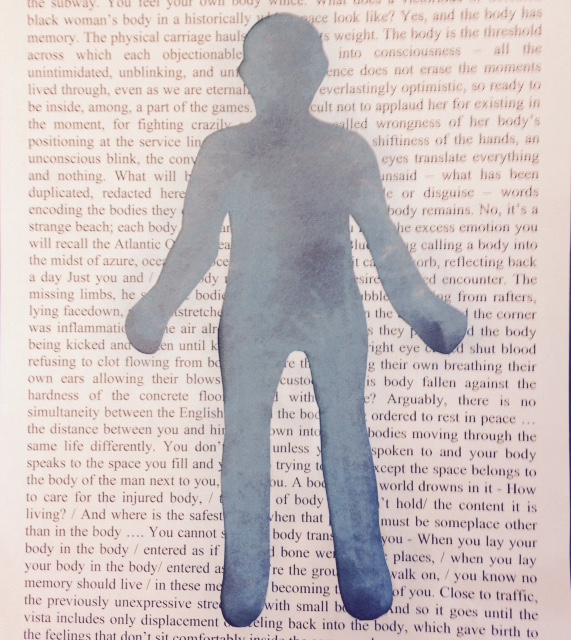

A final favorite is more intensely blue in the original than my photograph. The reader, Brittany Lloyd, wrote down all Rankine’s uses of the word “body” and discovered how often the word “blue” appeared in conjunction with it.

We discussed Citizen for more than four hours total, yet there were aspects of this collection we barely mapped at all. Citizenship, in all its possible meanings, remained at the margins of our attention. My personal response to the book remains raw, too. Rankine’s project reminds me of my own half-repressed angers, but she refuses to provide any simple answers or consolations. In the last sequence, she rolls down her window and eventually climbs out of the car to play tennis, signaling determined engagement, but she also turns away from conversation with a hostile stranger in a parking lot. “It wasn’t a match, I say. It was a lesson,” she tells her partner in the book’s last line, redefining conflict as education. Surely that’s one of the best reasons to teach this collection: Rankine’s determination to analyze and learn, her thoughtful negotiation of the obligations people have to one another and to their own well-being. Talking can be painful, but it’s better, most days, than brooding alone in our cars.

|

JOYCE CAROL OATES

|

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|