|

Vertical Divider

|

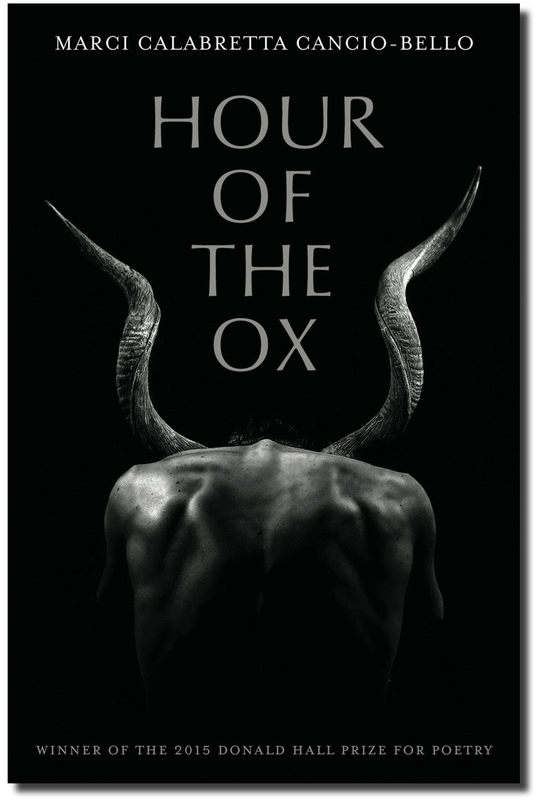

Hour of the Ox. By Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016.

ADVERTISEMENT |

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|