|

Imagine this: you grew up in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Like most kids, you're occasionally embarrassed, sometimes lonely, often confused. But between save points and furiously inhaled dinners, you carefully package these feelings, wrapping them in the complexity of youth, storing them deep inside for you to work through later, to grow with and to remain puzzled by well into adulthood.

You're older now. Sometimes, a friend drops the name of a popular video game, and you’re brought back to a moment. The time your dog died, and you mourned. The time your parents forgot to pick you up from school and you sat, stiff and too tired for the body of an eight-year-old, for three hours by your principal’s side. The time your friends liked your outfit. The time they didn’t. The time none of that happened. The time you lived your own life, made mistakes, were sad or happy or a mystifying mixture of the two.

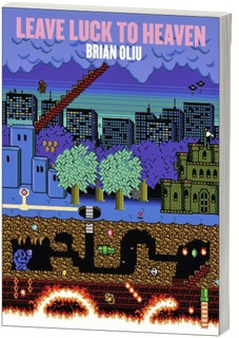

This is what Brian Oliu’s Leave Luck to Heaven is about: the way certain media can serve as sites of memory and coping mechanisms. The way video games become more than games; how they function as conduits through which our feelings pass.

Oliu's book, a collection of 32 lyric essays which takes its title from the rough and popular translation of the Japanese word Nintendo, serves, on the surface, as an ode to Nintendo-era games. But Leave Luck to Heaven is more than that. The essays are stunningly deep and dark, born from the realization that sometimes shit gets rough.

The essay “Simon’s Quest” captures this perfectly. Oliu describes a world filled with failure and blind hope, which is fitting, considering the essay's namesake is Castlevania II: Simon's Quest, a game whose unintuitive and unforgiving puzzles often polarize the gaming community. The game ranges from infuriating to unfair, a spot-on choice for illustrating the imperfections and injustices of the real world, which is hidden just beneath the surface of the essay.

“Simon’s Quest” aims to present a cycle, a story of equal parts, of sides: both acceptance and denial (of age, of change, of unfair mechanics, of limitations of the body and the mind). It does this by melding the experiences of the game’s protagonist, Simon, and the player, in this case Oliu. Both start, as the essay opens, “on a street in front of a church in a town that we do not know. There are stairs that we must climb and gaps to be crossed and no sense of direction except we must leave and walk into the forest.” While this establishes the world of Simon’s Quest in a literal sense, it also prepares the essay’s reader to enter Oliu’s world: a seemingly fumbling one characterized by confusion. The protagonist and the player are not the only people who populate this world, however. Throughout “Simon’s Quest,” villagers and villains from the game are pulled forward and dismissed, but “you and you and you” remain and evolve. At times, Oliu seems to address Simon as “you” (“You and you and you and I are old–backs are not what they used to be: yours from breaking candelabras in a castle…”) and, in those rare moments removed from Castlevania II, the “you” becomes someone closer and at risk (“. . . yours from moving couches from consignment shops to other people’s houses in hopes of leaving furniture behind before you leave this place for good . . .”). Oliu's essays aren't just for gamers, as each piece works toward two goals: paying homage to video games as well as capturing the non-gaming life of the player. “Simon’s Quest” the essay speaks to those familiar with the game—with its imagery of churches and castles and sneaky odes to complicated gameplay mechanics (“It is too much to go outside during the day, the sun and the music make things weaker and more susceptible . . . ”)—but larger than those elements is the sense of discovery and subsequent loss. The crux of the essay is not Oliu's poetic descriptions of the ways in which Simon’s Quest infuriates its player, but rather how Oliu relates the game to personal experiences and emotions. Time and time again, the poetic “I” speaks of aging (“You and you and you and I are old.”) and what it brings (“We win, but we are dead. We win, but we cannot bring back what we have brought back. We win and we are thanked.”). As the essay moves to its close, the language of death intensifies and repeats as the game world and the writer’s world eventually collapse in upon each other: “The day we begin to collect the things to put back together in order to destroy the sum of its parts is the day you tell us that they are taking you away from you and I am terrified of what is left to be said and what will be left of me at some point. The second we see where what appears to be ground is not where ground is, we line the path in front of us with prayers and holy water in hopes of seeing the fire at our feet or the sacramental flicker off screen.” The goal of Simon’s Quest is for its player to visit five manors and collect the parts of Dracula in order to revive and “destroy the sum of its parts.” And while this appears to be accomplished, the essay ends not with a sense of pride nor the game’s credits, but a “flicker off screen” that reminds the reader that Oliu’s essays are not solely about games. Leave Luck to Heaven greets its reader with two essays that are much more approachable for those unfamiliar with games than “Simon’s Quest,” which appears in the middle of the collection. The opening essay, “Super Mario Bros,” benefits from a video game title that has become well known in popular culture. Mario has been a household name for decades, a Nintendo tent pole spawning titles like Mario Paint and the recently released Mario Kart 8. “But our princess is in another castle,” a quote from Super Mario Bros that serves as a refrain throughout Oliu’s essay, has even risen to act as a cultural trope, Internet meme, and object of critical thought. It calls to mind situations in games, movies, and books, where an objective falsely appears to have been completed. In certain corners of the Internet, it’s a phrase used to mockingly or humorously point out a futile real world endeavor in which a person has misunderstood a task or misdirected their attention. Oliu gracefully picks up these notions of futility and desperation, employing the phrases “We are sorry” and “The princess is in another castle” before conjuring more private events for which the first person “we” apologizes. The plural “we” tells the story of unmet expectations and contemplation, and it is this plurality that propels the tension of the piece forward. Cleverly, the speaker and the spoken to are assimilated so that any reader unfamiliar with princesses and castles can still understand “Super Mario Bros”; the way a person “can explain how things work: the method, the pattern” and yet still be implored to “take pause,” to “Think of how you can be chased while standing still.” The second essay in Leave Luck to Heaven, “Rad Racer,” named after a title less recognizable than “Super Mario Bros,” shares similar obsessions with recognized and uneasy themes. In Oliu's hands, Rad Racer, a driving game about reaching checkpoints and avoiding car crashes, is elevated to something haunting: roads are asked to bear the weight of “the names of dead farmers and soldiers, the names of crops that died so that you can admire what is left of the barley as you wonder why the roads are lined with trees.” Cars become beds or boats or tractors. Movement and time become suspect. “When I wake up it is raining and the time is up and there is no movement,” writes Oliu. “In the dream where I wake up I am in my father’s car and no one is driving. My parents are on the front steps and they are waving goodbye as I try to open the door to get out.” The collection continues on in this way: hauntingly beautiful mash-ups of memories and pixels. The reader is confronted with monsters and ninjas, mothers and fathers. The unreality of gaming is always there, but the unreality of life is center stage, pushed to the forefront time and again. In many ways, Oliu has written a collection of essays that function similarly to the way a good game might: it will resonate differently with different sorts of people, and the experiences and memories the reader brings to the work will likely change his or her understanding of it. Like a favorite game or movie, Oliu has created something that you could share with another reader—another fan—and discuss all day without ever fully repeating the same lines and images you were drawn to individually. One thing is certain about Leave Luck to Heaven: this collection and this writer are doing tremendous work for video game literature. With modern gaming often being cast in a negative light, with society's concerns about the correlation between fantasy violence and real-life violence, the work being done by Oliu (as well as fellow game enthusiasts and writers, many of whom are published by online lit mag Cartridge Lit) is refreshing.

You will find violence and darkness in Leave Luck to Heaven, but not the kind that is shaped or influenced by video games. Rather, the violence and darkness are tethered to Oliu’s slippery language and keen ability to make the medium a vessel for his own conflicts.

Oliu demonstrates this in the penultimate essay, "The Final Boss" (which is titled not after a game but after the entity that drove the playing of early Nintendo games, the "big bad" waiting for the gamer at the end of the hero's journey), in language less subtle than what Oliu presents throughout the collection, perhaps inspired by the mental clarity and directness any good final boss demands:

Oliu begins Leave Luck to Heaven with an epigraph from Legend of Zelda, a line of dialouge spoken to the player by a Wise Old Man: “There are secrets where fairies don’t live." In other words, there exists a dark and syrupy magic to real life. Oliu, like many fine writers, has found his subject matter, his very own language, that allows him to uncover and showcase that magic.

|

Leave Luck to Heaven. By Brian Oliu. Uncanny Valley Press, 2014.

|

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|