|

Betsy Sholl's latest collection of poems, Otherwise Unseeable, evinces her abiding interest in the subject of music (especially jazz) and expands her previous engagement with political and social oppression. Her troubled musing on the ample history of victims of injustice is counterpointed—often dissonantly—with her impulse to relish the beauty she encounters in day-to-day life. In Otherwise Unseeable, the reader is presented with a mind attempting to find balance in a world that is greatly fallen but also greatly beautiful. One of the paradoxes of the human condition, as Sholl’s poems illustrate, is that the most beautiful music often rises out of the most devastating ruin.

Though Sholl’s subject matter is consistently “serious” (i.e., considering complex issues of history, psychology, aesthetic experience, and the life of the spirit), several poems in the first section playfully use characters from fairy tales (Rumpelstiltskin, frog and princess, woodcutter). These characters seem well-worn, however, and the poems don’t make them very fresh. It’s unfortunate that these poems are foregrounded in the first section, possibly dissuading some readers from continuing into the subsequent sections. Perhaps the author thought that the opening lightheartedness and the fantastical characters would draw readers in, but I have to admit that I almost gave up on the book as overly frivolous for my taste in several places in the first section—although I’m glad I didn’t. Some of the poems in the section also feel incomplete, reading like drafts of an idea for a poem rather than finished work, especially the opening poem, “Geneaology,” which is imagistically and linguistically interesting but seems too haphazard, like a draft to which the author didn’t dedicate enough revising or expanding energy. Although the poems in the later sections are more consistently complex, profound, and formally effective than those in the first section, there are a few poems from the opening section that merit attention. Two of the best show the influence of the Metaphysical poets. “Still Life with Light Bulb” and “The Wind and the Clock” wittily personify inanimate objects, and “The Wind and the Clock” presents a dialogue between them that is reminiscent of Andrew Marvell’s “A Dialogue Between the Soul and the Body.” In each of these poems, the objects seem to stand in, allegorically, for competing aspects of the self—perhaps that old body/soul dialectic, or the more modern concept of primal, animalistic instincts competing with more recently evolved faculties. From "Still Life with Light Bulb":

Another standout is “Wildflowers,” which opens with an epigraph from the book of Revelations, “And it was commanded them that they should not hurt the grass of the earth, neither any green thing”:

The poem illustrates the biblical theme that the last shall be first, sure, but it also communicates something of doom, at least for the human race, which has so thoroughly “hurt the grass of the earth” and every “green thing.” The grass of the earth will win out in the end, long after humans are gone, Sholl implies wryly.

“Argument,” the last poem of the first section, continues the dialogic approach of “Still Life with Light Bulb” and “The Wind and the Clock” and introduces this collection’s central dilemma—to dwell in and mourn the enormous tragedy of history, or to exist in the moment and offer up praise out of what T. S. Eliot called “timeless moments”? In Eliot’s view, these moments are the true substance of history, as opposed to major outward events and chronology. Sholl seems internally divided, instinctively viewing the sweep of history and the timeless moment as incompatible, contradictory. In her mental struggle, the speaker personifies nearby crows as a stand-in for one aspect of her self. They say, “For the sake of the dead, for the sake / of the murdered, don’t wax too eloquent / here under these dust-choked trees.” The following lines, in the speaker’s more immediate voice, give us the context for the dilemma: “Clear sky, seventy years since / Hitler invaded Poland.” In response to the “crows,” the speaker’s other self replies,

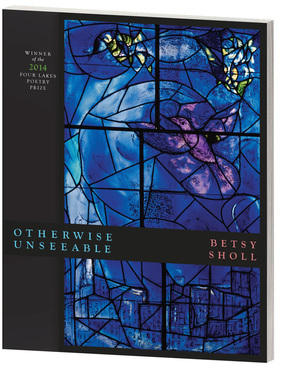

The first poem of the second section continues the meditation on this dilemma, taking Marc Chagall’s art as its subject. (The cover of this book features one of Chagall’s stained glass windows.) It’s important to note that Chagall was Jewish, and both of the World Wars occurred during his lifetime. In “What’s Left of Heaven,” Sholl writes:

For Sholl, Chagall’s work epitomizes the artist’s role of insisting on hope and beauty in the midst of a shattered world, not ignoring evil and suffering but in the face of it emphasizing the simultaneous existence of good. Sholl resolves the apparent dilemma between a historical consciousness and the experience of the timeless moment by fully acknowledging the reality and simultaneity of each. In this way, art seeks a balance between the tragedy and the comedy of the human condition.

Other historical figures who appear in these poems include the Polish-born Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, who died in a Soviet gulag, and the German Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was executed for his resistance to the Nazi government and a possible plan to assassinate Hitler. In the face of such historical atrocities as totalitarianism and genocide, Sholl does not resort to false comfort or deflect her gaze to more palatable subjects. There is no deus ex machina here: “God will not rise up out of war’s insane machine // to pull him down from the wooden platform, / halt the order to strip and walk barefoot // up the scaffold steps…” (“Prisoner Bonhoeffer”). It is this stark realism that makes Sholl’s songs of praise convincing. Realism does not contradict hopefulness in her poems; rather, the realities of a fallen world give fuel to the yearning for a higher reality. Music is Sholl’s favorite figure for this yearning, as in “U.S. Clamps Down on Pianos to Cuba,” in which the disenfranchised make music out of the imperfect materials they can muster:

Music is emblematic of the impulse to praise. In Sholl’s view, despite her earlier misgivings, praise in the context of violence and injustice is not an outrage but a necessity, the human expression of goodness and beauty in the face of a brutal world.

I stress the theme of music in the midst of oppression not to give the impression that this is the only recurring figure in this collection but that it is the most pronounced and most frequent. The poem “Shrines” is a fine example of a poem engaging oppression with figures other than musical ones. “Shrines” is a poem of alternating verse and prose stanzas (a stanzaic approach pioneered by Sherman Alexie, another poet concerned with oppression and its aftermath), occasioned by a visit to an Irish shrine to Saint Colum, where people leave all sorts of small items as tokens when they come to pray.

There is bitter sarcasm in the inmate’s statement, and despite the levity with which it is delivered, it is indicative of lost hope in a transcendent reality. The theme of hope in a transcendent reality is powerfully incorporated at the end of the poem in the setting of the Irish shrine:

The idea of invisibility introduced here calls up the title of the collection, Otherwise Unseeable, and the subsequent poem is the source of the book’s title. “At the Window” weaves together the idea of blindness, the invisible, and the sudden encounter with what was previously unseen or undetected:

By moving from a physical (and painful) encounter with an invisible reality to a spiritual (and traumatic) encounter with an invisible reality, the poem offers a metaphor elegantly through juxtaposition, without the common locutions that signal a comparison. The poem leaves unanswered the question of how an encounter with a transcendent reality occurs (“how did he come to see— / what shock, what light shattered the old lens?”), simply allowing the question to resonate in the reader’s mind, and the speaker turns to her immediate surroundings:

“At the Window” testifies to a faith in an “invisible kingdom” which we encounter in timeless moments—of trauma or transcendent beauty—which, like the air, we experience indirectly, through its effects rather than by direct perception. We cannot know, perhaps, how this happens, but we can realize that it does and that it changes us.

The final poem of the collection, “The Aging Singer,” affirms Sholl’s love of music and reasserts the paradox of encountering a seeming absence as a felt thing:

The song is “Please Send Me Someone to Love,” and the missing word, of course, is “love.”

Sholl’s poems suggest the possibility—and, thankfully, don’t insist—that we live in the midst of an invisible kingdom, which, like the air, surrounds and sustains us, even through the most horrific tragedies and injustices. This is not Pascal’s God-shaped void inside us so much as a presence that is always filling us, whether we notice it or not, like air with each expansion of our lungs. And if we do notice it and harness its power, it can become “breath entering the sax’s brass” (“Wood Shedding”)—the source of song, of transcendence. In her poems, Sholl struggles within herself over the seeming disparity of expressing joy or offering praise in the midst of a broken and suffering world, but in the end it is clear that she will not give up her songs of praise. One is reminded of a line by Adam Zagajewski: “Try to praise the mutilated world.” Sholl does so, and her voice invites us to join in—not in order to disregard the ruin of the world but to transcend it by refusing to believe it is the only reality, just because it is the most visible one. |

Otherwise Unseeable. By Betsy Sholl. Wisconsin University Press, 2014.

|

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|