|

Many poets have pointed out the flaws in trying to render and interpret history. “History,” as we come to know it, is largely written by the victor, interpreted, at best, by one person or group’s perspective and then translated through the ages as truth. But with every history, there are other stories and perspectives that should be brought to light and re-imagined. As poet Eavan Boland states in “Secrets,” from Domestic Violence, "It is because // the secret histories of things / deserve to linger, to belong again.”

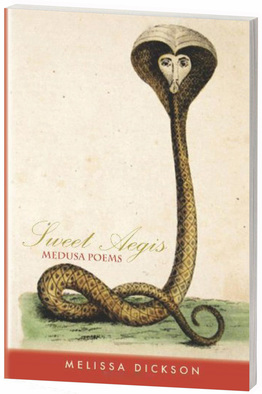

Sweet Aegis, a book of poems by Melissa Dickson, seeks to question the flaws in our interpretation not of history but of myth—particularly the story of how Medusa came to be the evil, snake-wielding monster who turns men to stone with her icy, penetrating stare. Dickson takes the reader on a brief journey, from Medusa's conception:

. . . to her rape by a greedy, young, and idiotic Poseidon—“She knew what she was up against, more than / the cold mosaic of my sister’s temple floor"—and further, to Medusa’s reflection of her fate—“King Midas has to touch to maim. / I cannot stop you from looking / any more than I can unsay my name.”

Dickson’s re-imagined Medusa is a beloved daughter “whose first word / was kitty, whose second word was Da-Da,” whose father, after “she is raped, disfigured, banished, beheaded,” endeavors to “re-dream her—hideous / from birth, undesirable, untouchable.” Medusa, the speaker in four of the collection’s poems and the subject of many others, seems to support such a reinterpretation in the poem “Medusa Argues Her Virtues":

At the end of the poem, the speaker asks, “Tell me—isn’t this / what you call a hero?” Here, Dickson forces the reader to acknowledge prior conceptions about the mythic figure and to question: has the retold myth fairly portrayed Medusa?

Sweet Aegis, however, sheds light on not only the Medusa narrative but also on a cast of other female characters from Greek mythology. Athena is cast as a “Bitch Goddess” who doesn’t have time or patience for anything but herself (“Please, I have my own problems”). In one poem, Andromeda buys a Hermes scarf “at that upscale consignment boutique / on Park and 82nd” and “won’t admit it’s secondhand”; in another, she recounts her wedding: “Naked and chained to a rock? Who wouldn’t want me? / My mother wept, my father waved his feeble sword.” Dickson uses such dark humor throughout the book to deal with stark mythic tragedies. Similarly, Dickson’s diction oscillates between formal and abstract—“Look to me, if you look / for absolutes; I am irreconcilable / change; in this I have not deceived”—and concrete authenticity—“There is cake. There are coconut macaroons / and a perpetual chocolate fountain,” largely depending upon the perspective of the poem’s speaker. Her poems' structures course from tight sonnets to fragmented quatrains to a visual poem (“Mercurial Mercury” follows a curved pattern). In one poem, Medusa dines in the Bullsboro Golden Corral, while “Prometheus robes the bones /in glistening fat.” In another, Perseus is re-imagined as something akin to a modern-day thug: “I had radical resources, mad swag, / a skullcap that made me invisible.” Dickson references modern culture as if to remind the reader that these poems not only reinterpret the Medusa narrative but also apply that flawed narrative to the daily predicaments of the modern woman. Perhaps in the poem simply titled “Ceto,” Dickson best conveys this idea:

Mythic women dealing with sexual abuse and subjugation surely is one of the prominent themes of Sweet Aegis, and it’s here that the Medusa narrative mirrors the struggles of modern women. When Rush Limbaugh called Sandra Fluke a “slut,” most thought the attack was ridiculous at best. Then, Dickson seems to ask, why do we still consider Medusa the monster? Isn’t it time that we question whether these mythic icons that permeate our culture possess the character traits they’ve come to represent?

As Dickson states in the fifth of her “Fragmented Quatrains,” “The most powerful force in the world is inconvenience.” Indeed, inconvenience fosters acceptance of status quo, of believing in whatever truths are force-fed. Often, it’s easier to believe in things as they are without questioning matters that may prove messy and difficult at best. As she writes in “The Medusa Effect,” “If you would labor to know / my gaze, it is not death you fear.” Perhaps what we ultimately fear is reconciling truth without stereotype, without preconceived notion beyond our own examination. In a culture that continues to objectify women, in a society in which the victim of sexual abuse is often blamed, in a country where date rape is contested and male legislators hotly debate who has control of a woman’s body, Dickson’s book is well timed and well placed. The poet forces the reader to shift her view of the mythological villain and asks her to abscond previous definitions of hero and victim. Ultimately, Dickson implies that each individual possesses the capacity to be both persecuted and victor when she writes: “None / perished at my gaze but at his own reflected” and “What she has / turned to stone was stone from the start.” Dickson peppers the book with quotes from Ovid, Hesiod, Nonnus, Aeschylus, and others, as if to remind the reader of the origins of the Medusa myth (and/or to educate the reader not familiar with the narratives). In the spirit of full disclosure, Dickson also includes a citation of sources read while crafting these poems, adding to her interpretation’s legitimacy. Most helpful, and all too rare in poetry collections, was Dickson’s own notes at the back of the book, which help to explain her thinking behind the poems and the Medusa myth. In this, Dickson admits, "My interest is a personal one, a quest, perhaps futile, to redeem one of Western culture’s most monstrous women.” With Sweet Aegis, Dickson accomplishes her mission with aplomb. |

Sweet Aegis: Medusa Poems. By Melissa Dickson. Negative Capability, 2013.

|

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|