|

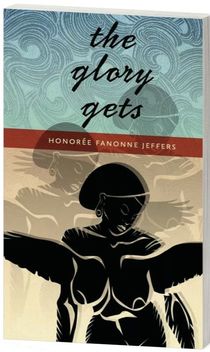

The day Honoreé Fanonne Jeffers's fourth poetry collection, The Glory Gets, appeared in my mailbox was the day a white supremacist sat in on a prayer meeting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston and executed nine people, six of whom were black women.

• • •

The woman depicted on the cover looks as if she has been stamped too many times without re-inking. She is winged. Her large breasts are both a burden of weight and the crux of her wings, simultaneously dragging her body downward and keeping it aloft. Her womanhood, then, is both her struggle and her strength.

• • •

I tell you this because when I held The Glory Gets for the first time, before I even spread the spine, it merged with current events in a way I will never be able to disentangle. It became, for me, the song of the voiceless. I looked to Jeffers’s poetry to do the difficult, impossible work of organizing the literal horrors around me. I opened it looking for answers.

• • •

In The Glory Gets, Jeffers approaches the subject of racial injustice determined but wary, acknowledging from the very first poem the pitfalls and difficulties she is up against.

“Singing Counter” is a poem of witness, responding to the triple homicide of Hayes Turner and his pregnant wife, Mary, in 1918. The poem acknowledges its own process as it unfolds; therefore, it exists less as a retelling of the tragedy and more as an interrogation of what it means to retell. We see Jeffers’s present-tense fatigue and anxiety flush against an act of violence from the past. We see her swerving to avoid dehumanizing clichés, stereotypical tropes, and the defensiveness of white people as she attempts to honor the memory of the murder victims with language that is honest. The poem begins:

Jeffers understands that if she is going to write about something as difficult and dangerous as what it means to be a black woman in America, the poetry must be as complex and nuanced as the subject itself. Times and spaces must be superimposed. Process must manifest in the product. Feeling must lie down with calculation.

“Avoid the tropes,” she demands of herself. Tell it straight. The implicit argument in this opening poem is that, when it comes to poems of witness, Emily Dickinson’s famous command to “tell it slant” does not always apply. There is a place and a need in poems of witness for naming, direct and unflinching statements, and clarity of thought. Jeffers seems to be arguing for an aesthetic of witness, one that relies less on “intellectual, fractured lyrics,” and more on clear, direct, narrative structures. It makes sense. If so much of the power of whiteness lies in the nebulous and unnamed way it permeates our lives, wouldn’t its poetic counter be naming and clarity? Before I go on, I want to make sure you understand that while Jeffers resists the desire for “intellectual, fractured lyrics,” there is no lack of intellect in Jeffers’s poems of witness, nor a lack of lyricism and complexity. While there are certainly straightforward moments, the poems as a whole writhe with music, tension, and surprising turns. “Singing Counter” is all at once a narrative, a meditation, a self-conversation, and a work of ekphrasis. She interrogates it all: herself, history, language, representation, and imagination. No one and nothing escapes the critical eye. It is this piercing gaze and courage that drives The Glory Gets. The courage to write this book, to name the systems of power that do not want themselves named. To dare, in the space of a poem, to experience life, power, and choice. • • •

Many of Jeffers’s poems in The Glory Gets haunt with eerie polyvocality. Sometimes there are literally several different voices in the poem (as in the dialogue between the speaker and her gynecologist in “Female Surgery”). Other times, polyvocality is achieved because the poem exists in conversation with other writers, such as Lucille Clifton and Wallace Stevens. In the “blues” section of the book, Jeffers achieves polyvocality by means of persona, writing from the perspective of Mary Magdalene.

In the lyric “Try to Hide,” Jeffers trisects the mind, the body, and the self. The self is the speaker of the poem, but even it has different voices. Short, italicized lines reveal moments where the self is hijacked by a different, more fragmented way of speaking. Visually, these segments look like an erasure, and the diction grows more and more strange and childlike as the poem progresses. In the beginning, the self says things like, “we’re in a church/ a field of scripture,” and “my body will fall/ on its back/ opening for the rack/ anonymous/ male sacrilege,” expressing complete thoughts with high diction. But by the end, the self sounds, bewilderingly, like this:

This regression is haunting and characterizes the adult self as encompassing a childlike subconscious. In other words, the more deeply the speaker probes notions of identity and memory, the closer it gets to a pre-verbal, infantile state.

“Try to Hide” is a mysterious poem, and I won’t pretend to be privy to all its meanings, but I do believe it enacts how the self fractures in response to acts of remembering. In conjunction with the work the rest of the collection is doing, I see this fractured self as the natural consequence of interrogating the difficult subjects of race, family, and history. To tell these stories, one must, to echo Whitman, be large and contain multitudes. The many voices of The Glory Gets remind us that this is a book preoccupied with, among other things, human communication. The ways in which we converse with members of our own race, with members of other races, with family, with dead people we never knew, with women, with men, with other writers, and—perhaps most importantly—with ourselves. • • •

People are always telling us that poetry is dead and disconnected from the real world. And yet there remain days of overwhelming feeling, like June 17, 2015, in which only poetry will do. The Glory Gets is a book that navigates the very real tensions and dangers pulsing under the surface of our everyday. It gives us an important gift: the silenced voice, singing despite its silencing—singing loudly.

|

The Glory Gets. By Honoreé Fanonne Jeffers. Wesleyan Poetry Series, 2015.

|

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|