|

Vertical Divider

|

Everything I Never Told You. By Celeste Ng. Penguin Press, 2014.

Little Fires Everywhere. By Celeste Ng. Penguin Press, 2017.

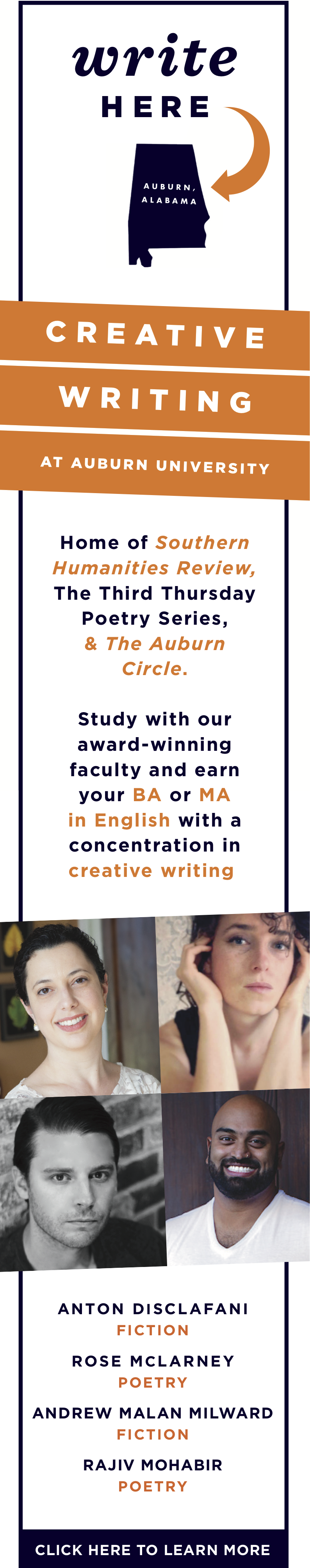

ADVERTISEMENT |

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|