|

Vertical Divider

|

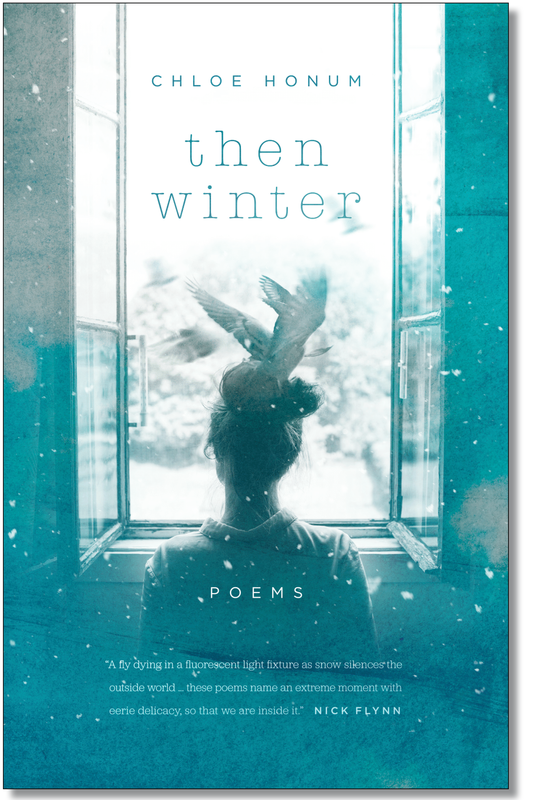

Then Winter. By Chloe Honum. Bull City Press, 2017.

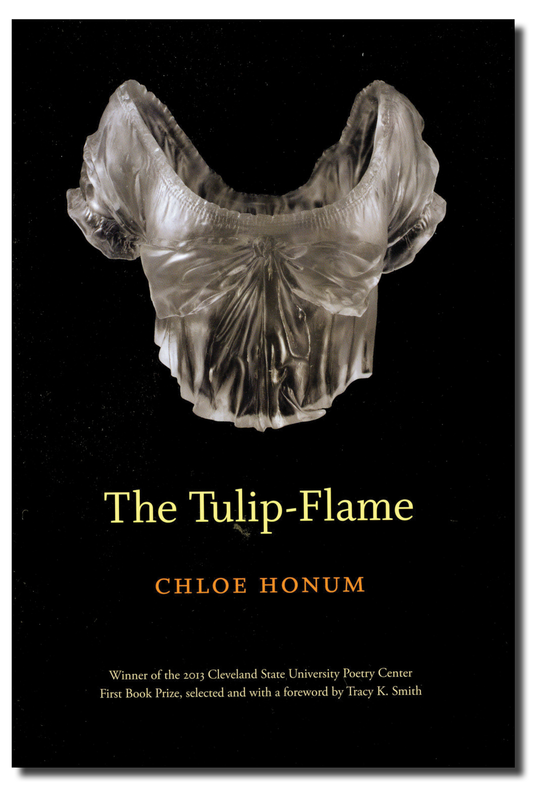

The Tulip-Flame. By Chloe Honum. Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2014.

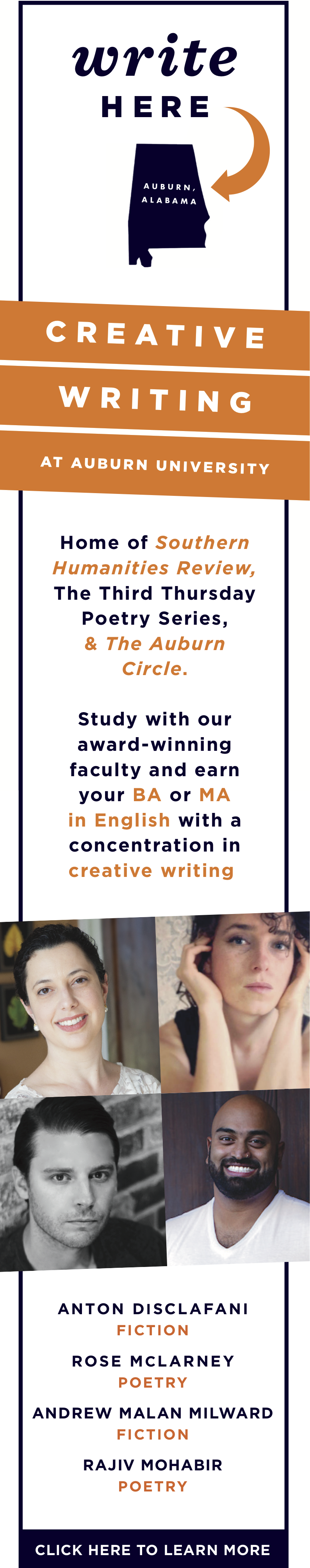

ADVERTISEMENT |

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|