|

Vertical Divider

Empathy is bullshit. At least that is what my cynical side believes some days. Often, when students say they empathize with a character in a novel or the speaker of a poem, they mean they engaged with the words at such a level that they experienced an emotional Freaky Friday and felt what it was like to walk if not a mile then a block or two in someone else’s shoes. Bullshit, I say, because it feels like a form of emotional tourism that lets someone understand another lived experience. Bullshit, I say, because the consumer of this tourism feels they’ve earned the badge of Well-Meaning Empathetic Person and can excuse themselves or erase their complicity in structures of institutionalized prejudice that benefit them.

But empathy is not solely to blame for the voyeurism of otherness. The cultural narrative of empathy is that it teaches us to be better humans. I used to like to say to my father that laws were for people without empathy because if you could feel what you were doing to another person, you wouldn’t do it. That sweet, idealistic young me may not be wholly wrong, but she’s not wholly right either. Empathy is something that makes us feel good about ourselves, how loving and accepting we are. We felt something while reading that novel or watching that movie, and now we get it. But it cost us nothing. And that’s the thing—if empathy is comfortable, you’re doing it wrong. •

This past spring, I taught a book I loved, Carol Ann Duffy’s The World’s Wife, to my advanced undergraduate poetry class. I was excited to talk about Duffy's use of sound and knew that the persona poems that her book would inspire would be more interesting than the usual fare. But when I got to class, my students were upset and wanted to talk about whether they loved or hated the book. The love/hate vote was split almost entirely along gendered lines. While I think whether or not someone likes a book is a tedious question, I decided to meet them where they were invested and asked what they didn’t like.

Men in the book were portrayed in a very unfavorable light, they said. Unfavorable. And yes, I agree that the men don’t look like knights in shining armor. And the female personas did terrible things also (like turn the bones of a dead beloved into a necklace and take credit for the mass murder of young boys). Women don’t exactly come out smelling like roses. When I tried to push the conversation toward elements of craft, I got responses like “rhyme is silly” and “I can’t take her seriously.” The discomfort with elements of subject matter bled into assessment of skill. They’d done so much better with previous books they all mildly enjoyed and weren’t offended by. I left class that day resolved not to teach the book again. But what the hell would be the point of that? •

Shortly after the debacle with The World’s Wife, I had coffee with Geoffrey Davis, who said something to the effect of, “everyone wants to feel empathy, but they want it to be comfortable.” It’s like Aristotle forgiving the poets Plato wanted to kick out of the Republic—it provides catharsis, and catharsis is both pleasurable and useful. But that terrible usefulness exorcises feelings to keep everyone content and satisfied with themselves.

I started to wonder if poems that provide a facile kind of empathy were doing a disservice. I needed to read—and teach—more poems that implicate the writer and/or the reader, that trouble, that contradict, that reveal unpleasant truths. •

The one compliment my class gave The World’s Wife and another mid-career book we read was that, in contrast to the books of poetry we read by younger, early-career poets, the older poets didn’t care if you liked them or not.

Perhaps this means there’s hope that we can age into a more radical empathy, by which I do not mean a greater forgiveness or a broader reach, but rather an empathy that feels uncomfortable and doesn’t try to fix that feeling. An empathy that doesn’t make us feel like a better person because our imagination could wedge itself into someone else’s shoes. An empathy without congratulation. Like Keats’s negative capability sitting in the unknowing, to start to trust the discomfort, examine it rather than escape it, test the tender spots with great feeling. •

“Which part of this book made you uncomfortable?”

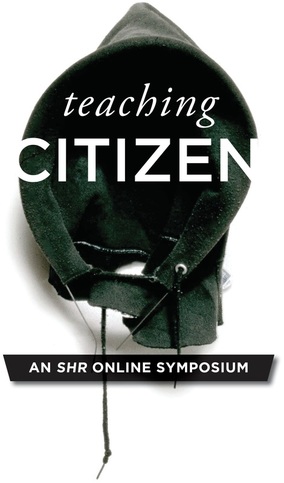

This was my first question for my students this semester when we discussed Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. There was a lot of flipping through the book and silence. It was uncomfortable. “The whole thing?” someone answered, unsure. That’s good, I thought. That’s a start. |

JOYCE CAROL OATES

|

CURRENT ISSUE

|

CONTACT

|

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

|